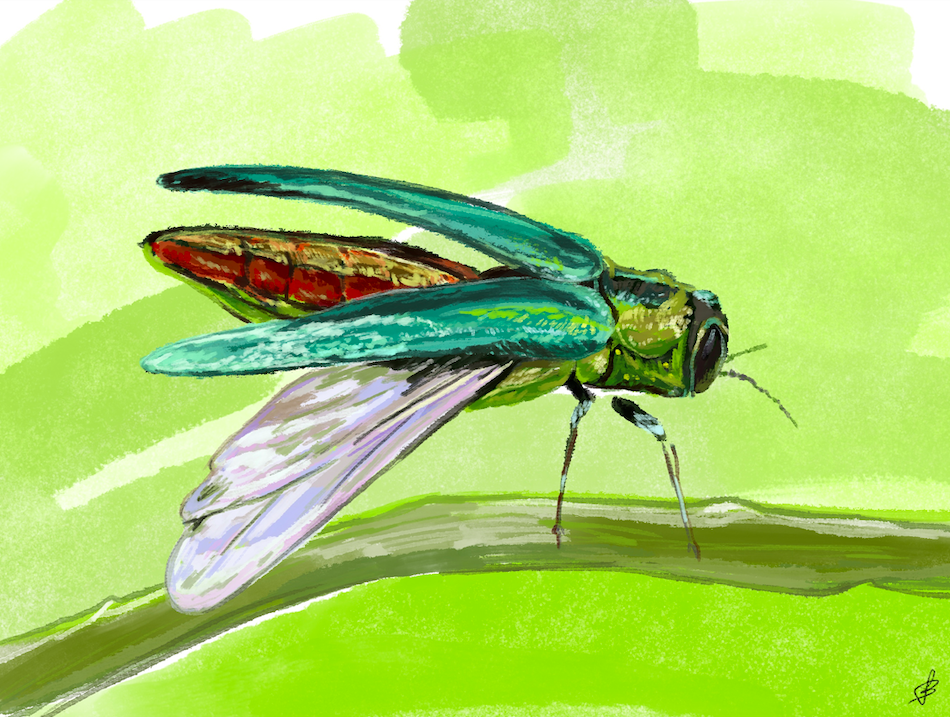

Illustration by Juli Badics

In October 2020, state officials discovered an infestation of emerald ash borers (EAB) in an ash tree near downtown Richmond. It was the first confirmed EAB infestation in Chittenden County, a sign that alarmed local foresters. By the time researchers found it, though, the invasive, brilliant-green beetles had likely been here for some time.

“[EAB] was only just detected, technically, earlier this fall. But that pretty much means it has been here for a while,” said Caitlin Littlefield, a forest ecologist and Research Assistant Professor at the University of Vermont’s Rubenstein School. “We don't have a very apparent infestation in terms of high mortality rates. But it can take up to five, six, seven, or even more years for the EAB to actually kill the plant.”

In Richmond, confirmed infestations are still limited to a handful of trees. But EAB is nevertheless a threat to local ecosystems, explained Chittenden County Forester Ethan Tapper.

“[EAB] kills a very high portion of all ash, most all of them. So, it's a threat to our biodiversity … it's a fundamental threat to the way that our forests work. Not just ash trees, but also all the natural processes and the other organisms that they support [are affected]. We believe anything that threatens our biodiversity is a fundamental threat to our forests,” Tapper said.

The first EAB discovered in the United States were in Michigan, found during summer 2002. They may have arrived from their native Asia in packing materials. Since then, the beetles, which feed on tree tissue, have appeared in 35 states and several Canadian provinces. They’ve destroyed hundreds of millions of ash trees.

Emerald ash borers are both slight and beautiful: Their green, slender bodies are just half an inch long. Larvae are bigger — about an inch and a quarter in length — with cream-colored bodies and brown heads. Trees they’ve infested may have thinning canopies, or new growth that is a sign of stress. When exiting trees in June and July, EAB leave behind small, D–shaped holes in the bark.

One way to combat the EAB is to remove all native ash trees. Ultimately that eliminates the resource the EAB relies on, eradicating them over time. It’s preferable to avoid harvesting trees when possible, though, Littlefield explained, because tree removal means losing vital wildlife habitat, shade, and oxy

gen production.

Preventative action is best for now, she said. That could include injecting trees with an insecticide that would kill off any EAB. “The good news is that there is an effective, naturally derived insecticide treatment that can keep ash trees alive forever,” Littlefield said. “[It’s] demonstrated to be very effective against the EAB but requires long term application.” Injections for the insecticide cost about $10 per inch in diameter and must be reapplied every three years.

Research is also being conducted on trees with possible genetic resilience against infestations. Tapper,

the forester, said nurturing more genetic variability within Vermont’s thre

e native ash tree species could help. Creating conditions that favor ash trees — such as openings the size of a quarter acre and removing trees creating shade — would support survival as well.

For now, Richmond is prioritizing trees that could pose a d

anger to the public. Many such trees are being removed by Green Mountain Power.

“[Green Mountain Power] have been coming through and cutting trees,” said Richmond Town Manager Josh Arneson. “They're taking care of ash trees that are dire

ctly underneath their power lines, which is a big help for us, because that means they are going to foot the bill to take care of those trees.”

Richmond has also applied for a $15,000 grant from the Vermont Urban and Community Forestry program. The grant wo

uld pay for treating or removing trees to mitigate EAB infestations.

Both Littlefield and Tapper recommend that landowners visit vtinvasives.org, where they’ll find a map of EAB in Vermont, as well as guidelines for responding to the invasive pest. Any at-risk trees near homes or power lines, or trees that may already be infested, merit a professional assessment. Experts agree being vigilant and planning for the future is crucial.